Educational and Reference Resources of the Tri-Canyons

Invasive Plants of the Central Wasatch

In this lesson:

- Healthy ecosystems of the Central Wasatch

- Introduction and spread of invasive plant species

- Impacts of invasive species

- How land managers control invasive species in natural areas

Learning objectives:

- Understand what makes an ecosystem healthy in the Central Wasatch, and list two major ecosystem services that are provided to the residents of Salt Lake City.

- Be able to explain how invasive species were introduced to the Central Wasatch and the main mechanisms of spread.

- Understand how invasive plants impact the environment.

- Know the three main control strategies land managers can use to manage invasive plant species.

- Learn about 7 specific invasive plant species in the Central Wasatch.

Healthy Ecosystems in the Central Wasatch

The Central Wasatch is a section of mountains and canyons right outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. Because of their proximity to a major city, these mountains typically receive 15 million visits each year. These visitors are picnicking, hiking, mountain biking, climbing, skiing, camping, and enjoying the wildflowers among many other activities. Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons are home to four world-famous ski resorts boasting the greatest snow on Earth.

There is something else about these mountains that make them very special and valuable to the people of Salt Lake City. 60% of the city’s drinking water comes from Big and Little Cottonwood Canyon watersheds. The majority of this water falls as snow, and is slowly released through the landscape, which acts as a giant water filter. The roots of trees and shrubs hold the soil and sediment in place, which reduces erosion and the soil particles themselves capture bacteria and microbes so that they stay in the soil, not in the water moving downstream. This remarkable, natural water filtration system saves the city of Salt Lake precious time and energy and allows the water to make it from the top of the canyon to people’s water faucets in just 48 hours.

Healthy ecosystems provide many ecosystems services such as accessible recreation and clean drinking water. What makes an ecosystem healthy? One measure of ecosystem health is biodiversity. Having a larger sampling of plant and animal species often means that when changes occur, the ecosystem can adapt. Resilience is an ecosystem’s capacity to absorb both natural and management-imposed disturbance but still retain its basic function so that it is able to behave in the same way over time.

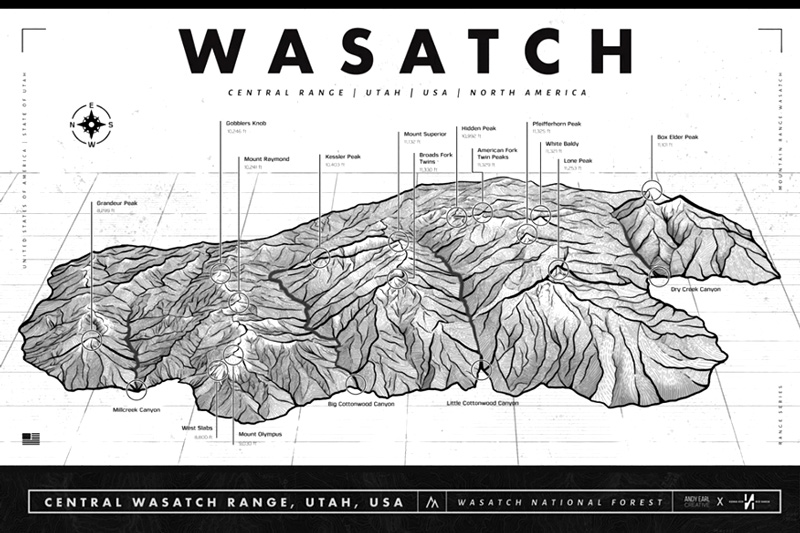

Map of the Central Wasatch as viewed from Salt Lake City, Utah:

Credit: Andy Earl Creative

Credit: Andy Earl Creative

An example of a diverse and healthy ecosystem in the Central Wasatch

An example of a diverse and healthy ecosystem in the Central Wasatch

Introduction and spread of invasive weed species

An invasive weed is a plant that has been introduced by humans to a given ecosystem and is causing environmental, economic, or human harm. Before humans, plants and animals have evolved and spread by natural processes. Ecosystems develop and change slowly, with checks and balances on population growth. Today, human beings often act as disruptors of natural processes in many ways, including transporting species vast distances. Sometimes this movement of plants is intentional: for agriculture, landscaping, or medicinal uses. Other times, these plants are transported accidentally on clothing, livestock, or in grain. Some of these intentionally or unintentionally transported plants have adaptations that allow them to spread rapidly, and they have no natural predators in their newly colonized ecosystem. Under these circumstances, human-introduced plants can become invasive.

Example: Dyer’s Woad, Isatis tinctoria

Dyer’s woad was brought to North America by early European settlers who used the plant to make a beautiful blue dye (as the name suggests). Blue coloration was hard to achieve before synthetic dyes were created, so this plant was brought from Europe for its use in textile coloration. Now, Dyer’s woad is considered an invasive species in much of the western US.

Credit: Noxious weed field guide for Utah

Credit: Noxious weed field guide for Utah

Once an invasive weed has been introduced by humans in a new ecosystem, how does it spread? Invasive species tend to spread voraciously by producing many seeds, using animals to transport their seeds, or spreading underground using horizontal stems called rhizomes.

Credit: Dyeing with woad

Credit: Dyeing with woad

Example: Myrtle Spurge, Euphorbia myrsinites

Myrtle spurge is an escaped ornamental plant (it was planted in people’s yards and now invades open spaces) that spreads aggressively by flinging its seeds up to 15 feet through the air!

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Example: Houndstongue, Cynoglossum officinale

Canada thistle is native to Europe, despite its misleading name. Each plant can produce 1,000-5,000 seeds that disperse on the wind AND a massive underground root system that makes this plant very difficult to eradicate.

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Impact of invasive plants

Invasive weeds are often the first plants to become established in areas of human disturbance such as new trails, ski runs, or picnic areas. They can creep in along roads and trails, following the movement of humans and disturbances. If unchecked, they can out-compete native species like many of Utah’s native wildflowers. Invasive species can also increase the risk of catastrophic wildfires, release toxic chemicals into the soil, and reduce our ecosystem’s resilience to disease, pests, and climate change.

Example: Phragmites, Phragmites australis

Phragmites create dense patches that spread by rhizomes and seeds, becoming a monoculture if left unmanaged. It thrives in moist soil near water but also has been found on dry, high-elevation slopes. In the wetlands around the Great Salt Lake, phragmites grow so densely that it changes the movement of water through wetlands and decimates migratory bird habitat. In 2011, 23,000 acres of Great Salt Lake wetland were covered by phragmites, which have been reduced each year through aggressive control measures such as burning, mowing, and herbicide.

Phragmites create dense patches that spread by rhizomes and seeds, becoming a monoculture if left unmanaged. It thrives in moist soil near water but also has been found on dry, high-elevation slopes. In the wetlands around the Great Salt Lake, phragmites grow so densely that it changes the movement of water through wetlands and decimates migratory bird habitat. In 2011, 23,000 acres of Great Salt Lake wetland were covered by phragmites, which have been reduced each year through aggressive control measures such as burning, mowing, and herbicide.

Credit: Utah Public Radio

Credit: Utah Public Radio

Example: Garlic Mustard, Alliaria petiolata

Originally native to Europe and most likely introduced as a culinary herb, garlic mustard can be eaten, and many gather it for pesto! The best way to identify this species is by smelling the foliage which has a strong garlic odor. Vegetative parts of the plant have allelopathic effects on surrounding plants, which means garlic mustard is releasing chemicals into the soil that make it hard for other plants to grow.

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Credits: Noxious Weed Field Guide for Utah

Management

Invasive plants can be treated in several ways, depending on the plant species, land regulations, and geography. One strategy is manual control, where plants are removed by hand. This strategy works best for plants with a central taproot that comes out of the soil entirely. Another strategy is chemical control, where herbicides are used at a particular stage of plant growth to either limit germination of seeds or seed production. Another possible strategy is biocontrol, where insects from the invasive weed’s native habitat are introduced to eat the invasive species.

Invasive plant species can be thought of as a ‘cancer’ in the ecosystem. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with them, they are just in the wrong place and growing out of control. This unchecked growth can wreak havoc on native ecosystems. Manual control is akin to surgically removing cancer cells. Chemical control is analogous to chemo treatment. It is best to catch new invasive species populations early through a management process called Early Detection, Rapid Response (EDRR).

Example: Dalmatian Toadflax, Linaria dalmatica

Dalmatian toadflax is an invasive weed that can spread by rhizomes and resprout when manually removed as well as produce 500,000 seeds per plant. Biocontrol is the most effective way to manage this plant: a stem-boring weevil eats the plant from the inside out!

Credits: Left: Noxious weed field guide for Utah – Right: www.insectimages.org

Credits: Left: Noxious weed field guide for Utah – Right: www.insectimages.org

What can you do?

No matter where you live, there are ways to get involved and take care of the land around you. Environmental stewardship refers to the responsible use and protection of the natural environment through active participation in conservation efforts and sustainable practices by individuals, small groups, nonprofit organizations, federal agencies, and other collective networks. Stewardship can be anything from checking your clothing and shoes for seeds after you finish hiking, picking up trash along a trail, or joining a volunteer event to pull weeds. Your actions and awareness make a big difference in protecting the ecosystems around you.

Questions

- Why are invasive species able to outcompete native plants and take over ecosystems?

- Do you think it is important to manage invasive species? Why or why not?

- What are some adaptations invasive species have that make them difficult to remove and manage?

- Imagine you are a land manager, tasked with controlling a new invasive species in your area. What information would you need to gather about the new invasive plant to design your management plan?

- Humans are responsible for moving plants around the world. Some of them become invasives. Do you think we are responsible for removing the invasives and restoring native biodiversity? Do you think a landscape that has been disturbed and dominated by invasive plants can be returned to a native ecosystem?