Educational and Reference Resources of the Tri-Canyons

Ecology in the Canyons: Amphibians

Let’s focus on amphibians:

– We will learn what is the Batrachology!

– Talk about what kinds of amphibians exist.

– Learn about the amphibians that live in our canyons.

– Explain their importance to our environment, and threats to the amphibians.

– Explore ways to help our amphibian friends.

– And other interesting topics, along with some exciting activities!

We hope that you will enjoy learning! You may use the Table of Contents to go directly to any specific topic.

Introduction: Batrachology

Can you guess what we’ll be studying this month? Amphibians, of course! Although bats might immediately come to mind, batrachology is actually the study of amphibians, and the word comes from the ancient Greek word for “frog”.

In the world, there are more than 6,000 species of amphibians! The largest of those is the South China Giant Salamander that grows up to 5 feet 11 inches long! How do you compare to a salamander that big? The smallest amphibian, Paedophryne amauensis, is a frog from Papua New Guinea that only gets to be about 0.3 inches long! While we wouldn’t find either of those incredible amphibians here, the United States does have around 300 species of amphibians and we have around 15 species here in Utah! While we can’t boast the largest or the smallest, we do have some amazing amphibians right here in the state.

These special, secretive creatures play an important role in local ecosystems, tell us quite a bit about the health of their environment, and they’re always a thrill to spot in the wild! Before you head out to look for some amphibians, we’d like to give you some reminders on good outdoor etiquette. Please don’t touch any amphibians that you find. We’ll talk about why later on, but it is best to enjoy them with your eyes only. Also, in general, it is never a good idea to take animals out of the wild. You might think they would make a good pet, but it is always best to leave them in their natural environment. Also, if you are in the canyons, please remember that you are in a protected watershed – this means that skin-to-water contact is not allowed.

Spring and summer is the best time to look for amphibians, and here are some tips on places where you might consider looking for some:

- You can often hear the calls of Western chorus frogs near the Brighton Store and around the loop closer to Brighton Ski Resort in Big Cottonwood Canyon.

- You might spot Boreal toads around shallow lakes or ponds in the canyons. Easier lakes to access include Silver Lake and Willow Heights in Big Cottonwood Canyon. More strenuous hikes can take you to Red Pine or White Pine lakes in Little Cottonwood Canyon. If you hit the trail, remember to bring water and adhere to Leave No Trace principles.

- If you head up to Cecret Lake in Albion Basin, those aren’t fish you see in the lake! They are tiger salamanders!

A variety of amphibians can be found in the Valley, and you can even see some at the Hogle Zoo and the Loveland Living Planet Aquarium.

What is an Amphibian?

Amphibians include animals like frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians, and they all share some characteristics that set them apart from other creatures. We’ll talk about a few of them in this section. Before we get started, what do you know about these animals already?

All amphibians are considered vertebrates. This means that they have backbones. Do you have a backbone? Would that also make you a vertebrate? The answer is yes! What are some other groups of animals that have backbones? Reptiles (like snakes, lizards, and turtles), mammals, birds, and fish all have backbones, too. A creature without a backbone would be called an invertebrate. Can you think of any creatures that would be considered an invertebrate? Examples can include worms, spiders, and snails!

Amphibians are also cold-blooded, a trait that they share with reptiles. Cold-blooded animals cannot regulate their own body temperature, and must rely on external factors to control their internal body temperature. On a chill day, they might move to a sunny spot to bask. On a hot and sunny day, they might move to a burrow underground to cool off. Cold-blooded animals are also called ectotherms. Are humans cold-blooded? No – we can regulate our own body temperatures. Do you know what the average human body temperature is? It is 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. All mammals (including humans) and birds are warm-blooded, or endotherms.

There are some shared characteristics that only amphibians have:

- They live a double life! No, not like a secret agent. Amphibians live part of their life in the water, and part of their life on land! What kind of special adaptations would they need to help them do this? We’ll come back to this idea a little bit later!

- They have thin, moist skin! We also say that it is permeable. What would some advantages and disadvantages be for having very thin, moist skin? What can that tell you about where these creatures need to live? Amphibians don’t need to drink water like we do, they can absorb water through their skin. However, this means that they can lose water as well so they need to live in wet or moist environments in order to stay hydrated. Amphibians also have mucus glands that produce a layer of mucus, this mucus covers their bodies to help them retain moisture. Now take a deep breath. What organs do we use to breathe? Our lungs! In addition to breathing with their lungs like we do, an amphibian’s permeable skin allows them to breathe through their skin. Some amphibians don’t have well-developed lungs, and some species don’t have lungs at all! One disadvantage of their thin skin is that they are very sensitive to chemicals in their environment, since they can easily absorb them into their bodies. This is why you shouldn’t touch or pick up amphibians – you might accidentally have something on your skin that could make them sick.

- They lay eggs with no shells! Have you ever cracked an egg while baking? If so, you’ll be familiar with the hard shell that encases the egg. Other than birds, reptiles and amphibians lay eggs. Reptiles like snakes and turtles lay eggs that have a leathery shell. Amphibians lay eggs that have no shell. They are gelatinous. If you have some chia seeds at home, mix some with a little bit of water and wait for 5 minutes. What does it feel like? If you laid eggs that were gooey and didn’t have shells for protection, what kind of place would you want to lay your eggs?

So our amphibians have backbones, are cold-blooded, live part of their life in the water and part of their life on land, have permeable skin, and lay gelatinous eggs. With these things in mind, what do you think a good habitat for an amphibian would look like? Take notes in the student guide or draw a picture in your notebook. Recall that a habitat provides food, water, shelter, and space.

Types of Amphibians

Frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians are all amphibians. In this section, we’ll talk a little about each group.

- Frogs: Frogs have smooth skin, short bodies, long legs, bulging eyes, and many have webbed toes. They have 4 toes on each of their front feet, and 5 toes on each of their back feet. As adults, frogs do not have tails.

- Fun Fact: About 90% of amphibians are frogs! If we estimate that there are 6,000 different species of amphibians, can you do the math to figure out 90% of 6,000? Approximately how many species of frogs are there? Answer: 5,400.

A green frog at the edge of the Coldwater Spring reservoir by NPS/Gordon Dietzman, (n.d.). Public Domain

A green frog at the edge of the Coldwater Spring reservoir by NPS/Gordon Dietzman, (n.d.). Public Domain

- Toads: All toads are frogs, but not all frogs are toads! While that might be a bit confusing, let’s think of it another way. Think about all the yummy vegetables that you like to eat. Now picture a carrot. Carrots are vegetables, but not every vegetable is a carrot. There are also zucchini, potatoes, broccoli, peppers, and more. Carrots are just one type of vegetable, just like toads are just one type of frog. So what sets toads apart from frogs? A toad’s skin has warts and tends to be drier, while a frog’s skin is smooth and slimy. Can toads give you warts? No! But, all toads are actually poisonous. They have special parotoid glands behind their eyes that secrete a toxic substance! Most toads are only mildly toxic to humans, but if you touch a toad be sure to wash your hands with soap and water. Another difference is that toads tend to have shorter, stockier legs that are better suited for crawling and burrowing. Frogs have long, strong back legs that are better suited for leaping. Looking at the photos, what are some other ways that you can tell the difference? How would you describe them to someone else?

2018 Photo Contest Winner Flora & Fauna Category by Peggy Yeager, 14 April 2018. Public Domain

2018 Photo Contest Winner Flora & Fauna Category by Peggy Yeager, 14 April 2018. Public Domain

- Salamanders: Salamanders have long slender bodies, short limbs, and long tails. While this means that they often resemble lizards, salamanders and lizards are very different. Since salamanders are amphibians they have smooth, moist skin and not dry, scaly skin like lizards have. If you look at their feet, they have soft toes without claws. Most lizards have claws on their toes.

Eastern Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) by Peter Paplanus is licensed by CC BY 2.0

- Newts: Similar to the situation with frogs and toads, all newts are salamanders but not all salamanders are newts. Newts tend to spend more of their time in the water than salamanders, and are considered semi-aquatic or aquatic. Because of this, they are better adapted to life in the water. Most newts have webbed-toes and a paddle-like tail to help them swim. Newts also tend to have skin that is drier and rougher than salamander skin.

Rough-skinned Newt by Peter Pearsall/USFWS, 19 December 2015. Public Domain

- Caecilians: Caecilians are amphibians that do not have arms or legs! In fact, they look more like a worm, eel, or snake. Caecilians are only found in tropical regions of South and Central America, South Africa, and Southeast Asia. Even though they are amazing amphibians, you unfortunately won’t find one here in Utah!

Caecilian (Gymnopis multiplicata) by Ian VanLare is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Life Cycles

The word “amphibian” comes from the Greek word for “double life”, and as we mentioned earlier this refers to the fact that they spend part of their life in the water and part of their life on land. Eggs are laid in the water, tadpoles hatch and grow underwater, and adults leave the water for a life mostly spent on land. Adults return to the water to lay their eggs, and the cycle begins again.

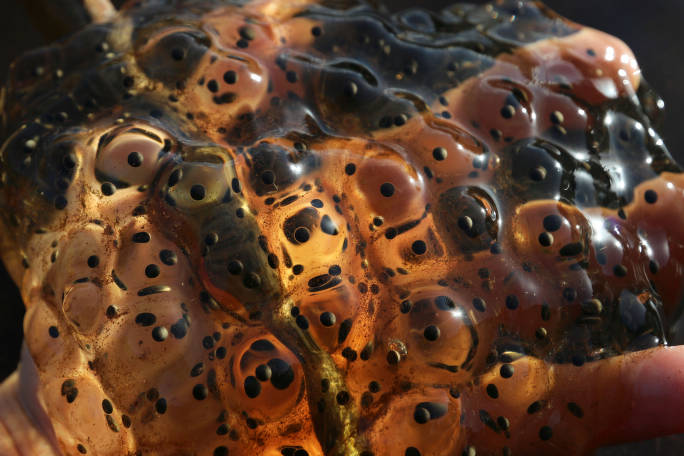

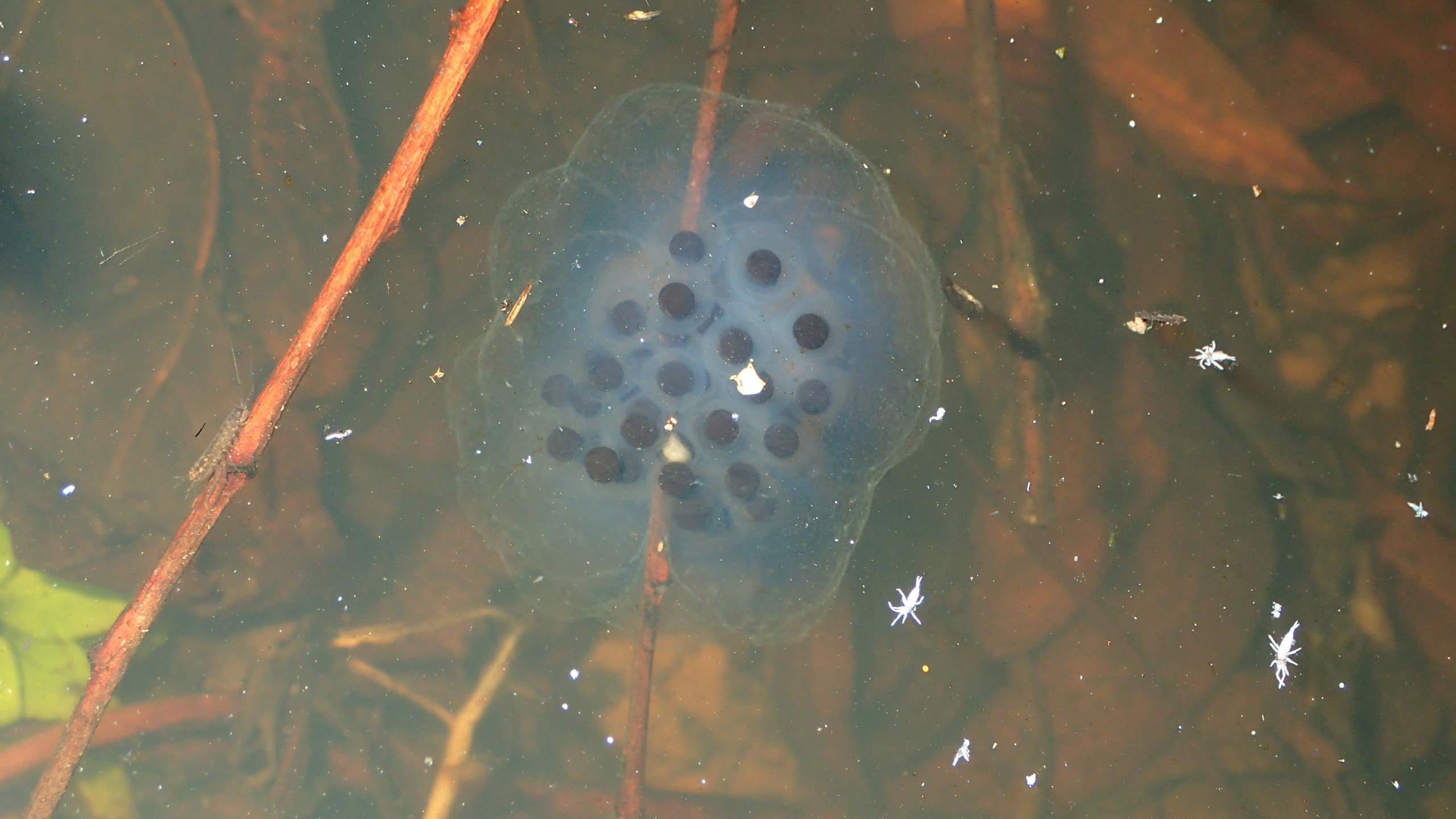

Amphibian eggs are laid in the water, often tucked into aquatic vegetation in a part of the pond that is calm and hidden away from any predators. Though all amphibian eggs are soft and without shells, you can tell frog, toad, and salamander eggs apart if you know what clues to look for! Look at the photos below. How would you describe each photo?

Red-legged Frog eggs by Peter Pearsall/USFWS, 10 August 2018. Public Domain

Toad-spawn by Mike Krüger is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

Salamander egg mass by Tom Mann, 6 February 2018. Public Domain

Frogs lay their eggs all together in a cluster while toads lay their eggs in a chain. Like frogs, salamanders lay their eggs in a cluster but salamander eggs have an extra jelly-like layer around them.

Once the eggs hatch, the larvae live underwater for a time. At this stage they have gills to breathe, tails to help them swim, and they do not yet have legs. Frog and toad larvae are called tadpoles, while salamanders are just called juveniles or larvae. Take a look at the photos below. How would you describe them? What is similar and different?

Tadpole by Rob is licensed by CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Tadpole at Mystic Lake by brewbooks is licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0

Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) Larva by Brian Gratwicke is licensed by CC BY 2.0

The tadpoles that are completely black are toads, and the ones that are greenish with gold flecks are frogs. The salamander larvae have longer bodies and have gill buds where their feathery external gills will grow.

As they grow, frogs and toads develop their back legs first while salamanders develop their front legs first. Eventually the frogs and toads will grow their front legs and their tails will start to shrink – at this point in their lifecycle they are called froglets or toadlets. Likewise, salamanders will start to develop their back legs.

- Frog/Toad:

Tadpole 3 by B kimmel is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

Tadpole 5 by B kimmel is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

Tadpole 6 by B kimmel is licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0

- Salamander:

Eastern tiger salamander, larvae 25 by Sam Stukel/USFWS, 1 July 2019. Public Domain

Eventually, they will lose their gills and develop lungs. Frogs and toads will lose their tails completely, while salamanders will retain them. As adults, they leave the pond and pursue a life mostly spent on land. Since they have permeable skin they do still need to live in moist environments, though they won’t live in the water all the time like they did as larvae.

As the seasons change and the weather gets colder, cold-blooded animals like amphibians have a harder time regulating their body temperature. So what do they do in the winter? They brumate! Brumation is very similar to hibernation. We use the word hibernation for warm-blooded (endothermic) animals, and we use the word brumation for cold-blooded (ectothermic) animals. During brumation, an animal’s breathing, body temperature, heart rate, and metabolic rate all slow down. Boreal toads pass the winter in mammal burrows or even beaver dams. Have you ever spotted beaver dams in the canyons or in the valley? You can see two beaver dams at Silver Lake and one near Reynolds Flat in Big Cottonwood Canyon. Western chorus frogs and Western tiger salamanders will also utilize mammal burrows to overwinter. The place where an amphibian brumates is called a hibernaculum.

After brumation, amphibians will migrate from their non-breeding sites to local bodies of water where they will find a mate and lay their eggs. At this point, the life cycle will begin all over again.

For more on Amphibian Lifecycles, try the “Do You Know How an Amphibian Grows” from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums:

ENGLISH:

ESPAÑOL:

What Amphibians are in the Canyons?

In the last section we mentioned that frogs, toads, salamander, newts, and caecilians are all amphibians. Here in Utah we only have frogs, toads, and just one species of salamander. Up in the canyons, however, we really only have three species of amphibians: the western chorus frog, boreal toad, and western tiger salamander. In this section, we’ll learn about each of these creatures and how to identify them!

- Western Chorus Frog

Captive Boreal Chorus Frog – Brown Morph by Charles (Chuck) Peterson is licensed by CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

-

- How to ID:

- Primary color varies, can be brown, olive, gray-green, or tan.

- Prominent black stripe that extends from their nostrils, through their eyes, and down each side of their body.

- Three darker stripes that run down their back; stripes may be continuous or broken up.

- Cream-colored belly.

- Size: Only about 1-1.5 inches in length.

- Habitat: Near quiet bodies of water, often in association with wetland meadows and forests.

- Diet: Terrestrial (land-dwelling) insects, flies, spiders. As tadpoles they mainly eat aquatic (water-dwelling) plants.

- Behavior: At higher elevations, they are most active in the late morning and early afternoon and during breeding season they will call at dusk and into the night.

- Fun Fact: The male chorus frogs call to attract the female frogs during breeding season. Their calls are very recognizable, sounding like someone running their thumb along the teeth of a comb. If you have a comb at home, try it out! Have you ever heard a noise like that outside?

- Lookalikes: Luckily, the western chorus frog is the only frog that has that prominent black stripe through its eyes.

- For more on frog calling, check out the K-4 or 5-8 lesson plan from the National Wildlife Federation.

- How to ID:

WILDLIFE FED LESSON PLANS: Call of the Wild (K-4):

WILDLIFE FED LESSON PLANS: Call of the Wild (5-8):

- Boreal Toad

Boreal Toad (Bufo boreas boreas), juvenile (~2 yrs old) by N. Stuart is licensed by CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

-

- How to ID:

- Gray to greenish body.

- Warty skin.

- Dark blotching on back and belly.

- Pronounced, cream-colored dorsal stripe (“dorsal” refers to an animal’s back, so a dorsal stripe is a stripe of color that runs down the toad’s back).

- Large oval parotoid glands.

- Size: Can grow up to 4 inches.

- Habitat: Found at high elevations throughout most of Utah near slow moving streams, and wetlands, ponds, lakes, meadows, and woodlands. They have a preference for water with sloped banks.

- Diet: Small invertebrates like ants, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, and worms. As tadpoles, they mainly eat algae and detritus (detritus is dead plant and animal matter).

- Behavior: They are active in the day or at night.

- Fun Fact: Boreal toads do not have vocal sacs, which means that they cannot sing! They can produce a quiet, chirping sound. However, this means that if you hear any amphibian calling or singing high up in the canyons, you know that it is a Western chorus frog!

- Lookalike: Woodhouse’s Toad. Similar in that they both have the cream-colored dorsal stripe, but the Woodhouse’s toad is a little bigger, growing up to 5 inches. The Woodhouse’s toad lives at lower elevations, so they are not likely to overlap in their range. So if you think you’ve spotted a Boreal toad near your home or school in Salt Lake, or at a location lower in the canyons, it is very likely a Woodhouse’s toad! If you know the elevation of where you’re at, Boreal toads tend to only live higher than 7,000 feet while Woodhouse’s toads lives below 7,000 feet. Another difference is that Woodhouse’s toads do have a vocal sac, and their call sounds a bit like a sheep!

- How to ID:

Woodhouse’s Toad by Andrew DuBois is licensed by CC BY-NC 2.0

- Western Tiger Salamander

Tiger Salamander by Pipe Spring National Monument/NPS, 10 July 2013. Public Domain

-

- How to ID:

- Olive, brown, or black body.

- Tan or yellow spots, blotches, or stripes.

- Broad head, small eyes.

- Long, slender body with a long tail.

- Between 11 and 14 costal grooves on each side of their body.

- Size: Tiger salamanders are the largest terrestrial (land-dwelling) salamanders, growing up to 14 inches in length.

- Habitat: Tiger salamanders live in a wide range of habitats from sea-level to 10,000 feet, provided they are able to burrow and stay moist, including mountain forests and meadows.

- Diet: Adults will eat just about anything they can get in their mouth, including insects, worms, slugs. Larvae will eat aquatic invertebrates and even other amphibian larvae.

- Behavior: These salamanders spend most of their time burrowed underground, but will emerge at night. Tiger salamanders can dig their own burrows, or they’ll use a burrow made by a rodent or other small animal. They’ll migrate to wetlands during the fall in preparation for the late winter/early spring breeding season.

- Fun Fact: Typically, tiger salamander larvae will metamorphose at the end of their first summer season. If conditions are not favorable, they will retain their gills into adulthood and spend the rest of their life in the water. This is called neoteny. These salamanders are called neonates, or paedomorphs, and they are more common at higher elevations.

- Lookalike: None. Western tiger salamanders are the only species of salamander in Utah.

- How to ID:

In the valley, around your home or school, you may see – or hear – some different amphibians. Use the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources’ Utah Species Field Guide to check out the other amphibians that live here in Utah. Use the scavenger hunt in the student guide to become more familiar with local species.

Find a spot outside near your home, school, or local park. Would this spot be a good place for an amphibian to live? Why or why not? Would it be able to get everything it needs from its surroundings? What else could this spot have to make it a good habitat for an amphibian? Try this exercise in a few different locations. Return to these spots in the spring and summer and see if you can find any evidence of amphibians.

Now that you’re familiar with the frogs and toads found here in Utah, make your own from a recycled paper roll. You can decorate your new friend however you’d like, or you can decorate it as one of our native amphibian species!

Why are Amphibians Important?

If you followed along with Trails Online last year, we talked about an ecosystem being a community of living and non-living things all interacting together. What kind of role do you think amphibians play in their ecosystems? In their interactions with other living things, they are important as both predator and prey. At various stages of their life cycles, amphibians eat aquatic vegetation (plants), insects, invertebrates, and vertebrates. In turn, they are consumed by animals like fish, snakes, birds, and a variety of mammals. They play an important role within local food webs, especially because they are a part of both aquatic (water-based) and terrestrial (land-based) ecosystems.

Amphibians are also a good indicator of ecosystem health. Because they can absorb things through their skin, they are sensitive to pollutants like pesticides. In some instances, the presence of pesticides has caused deformities like extra legs. Beyond that, amphibians are impacted by other factors like habitat loss, non-native or invasive species, drought, and disease. Changes in where amphibians are living, how many are in an area, and how many different species are in an area can all provide clues about the health of an ecosystem or habitat. The Cottonwood Canyons are both protected watersheds since the water from those canyons provides drinking water to homes and schools across the Salt Lake Valley, so water quality is pretty important! Having a variety of amphibian species and having healthy populations of amphibians is a good indicator that our water is clean and healthy. In our canyons, benthic macroinvertebrates also serve as indicator species for aquatic ecosystems. We talked about this idea in last year’s Trails Online: Ecology on the Trail program during Week #2 on Habitats. You can refer back to that week’s presentation, or you can view the Bugs and Water Quality activity here:

Bugs and Water Quality Activity

Threats to Amphibians

Globally, amphibian populations have been in decline. If you navigated through the Utah DWR Field Guide mentioned earlier, you’ll likely have noticed that many species here in Utah are experiencing population decline (and some are no longer found in Utah at all!). What could be threatening our populations of amphibians? While many factors can be at play, the biggest factors are habitat loss, disease, and climate change.

Amphibians need terrestrial and aquatic habitats, so habitat destruction or degradation to either is bad news for amphibian species. When a habitat is destroyed or degraded, it can no longer support the species that once lived there. Habitat loss can be caused by many different things, one of them being urban development. The construction of houses, businesses, and roads can impact terrestrial habitat or displace aquatic habitat. Sometimes, development can create hazards that prevent amphibians from being able to migrate from their non-breeding sites to their breeding sites. Recall that amphibians breed near water and lay their eggs in the water. Without a healthy and safe water source, amphibians are not able to reproduce. Aquatic habitats can also be impacted by things like water pollution.

Another threat to amphibian populations globally is the chytrid fungus. This fungus infects the animal and affects its skin, causing it to thicken. Remember that an amphibian’s thin, permeable skin is important in helping them absorb water and oxygen. Thicker skin does not have this ability and it impedes the amphibian’s ability to maintain water and oxygen levels. Around the world, this fungus has even caused the extinction of some amphibian species.

Drought and climate change are other factors that impact our populations of amphibians. Since amphibians rely on bodies of water to reproduce, what would happen if all of the good breeding pools dried up? Eggs must be laid in the water and tadpoles grow and develop underwater, and without water these parts of the lifecycle are not possible.

Climate change will likely make droughts worse, further threatening amphibians. Remember that amphibians need to live in a moist environment to stay hydrated. Certain species are adapted for living in hot, dry places like the desert, but climate change may happen faster than other non-desert species can adapt. It is also possible that temperatures may become too hot and dry for certain species, despite their ability to burrow underground to escape the heat.

To explore the impacts of climate change on amphibians and on your own life, use the lesson plan for the Climate Change activity from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

Ways to Help our Amphibian Friends

Based on what we have talked about already, what are some ways you think that you can help amphibians in your everyday life? List them in the student guide before reading the following.

Here are some things you can do to help amphibians:

- Learning about local amphibians. Being aware of the beauty and diversity of local species and the threats that face them is an important step in helping conserve them. Sharing your knowledge with family and friends is another great thing you can do!

- When you’re outside, keep an eye on where you are stepping. Some amphibians, especially as they are growing and developing, are very tiny!

- No matter where you are, you can be mindful of what you might be introducing into local waterways, including things like fertilizers, pesticides, bug sprays and even sunscreens. In the canyons, you can observe the rules of the protected watershed. That means leaving your dogs at home when you visit the canyons, and by not swimming or wading in the water.

- If you see a frog, toad, or salamander, don’t touch them! Since they have their special permeable skin, they are very sensitive to anything that might be on your hands like sunscreen, lotion, hand sanitizer, or bug spray. It is best to enjoy them with your eyes only.

- Avoid taking any animals out of the wild to keep as pets. It is best to leave them in their natural environments.

- You can maintain natural spaces in your yard or schoolyard – things like leaf litter, logs, and rocks all can provide shelter for amphibian species in the valley.

- Avoid walking or driving through any bodies of water or wet meadows. Not only does this reduce the risk of amphibians being trampled, but it helps to conserve their habitats.

- If you are in or around bodies of water, you can take care to decontaminate any equipment to help prevent the spread of disease. An adult can help you prepare a 10% bleach solution to decontaminate, and you can let your things air dry.

- Citizen Science: Another way you can get involved is to participate in Citizen Science projects, and there are a few organizations here in Utah that are doing some pretty awesome work to help our Utah amphibian species. One project is the Amphibian and Aquatic Habitat Assessments project that is a partnership between the Sageland Collaborative, Utah’s Hogle Zoo, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah Geological Survey, and the U.S Forest Service. Volunteers help collect data about frogs and toads at all stages of their lifecycle, as well as collect water quality samples, to help better understand and conserve amphibian habitats. With an adult, you can join in on a survey or sign up to monitor a specific site. The Hogle Zoo’s Center for Boreal Toad Conservation helps monitor populations of Boreal toads near Bryce Canyon National Park. They also have a small population of toads that will, in the future, hopefully help re-establish boreal toad populations in that region. The Loveland Living Planet Aquarium has a similar program, and they released their first captive-bred toads this past July!

If you find yourself outside often and you or your adult have a mobile device, the Amphibians of Utah app is a free app to download that was created by the Hogle Zoo and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources – it is a field guide and it lets you submit sightings of amphibians.

For more information on these programs, please visit:

https://sagelandcollaborative.org/aquatic-habitat-assessments

https://www.hoglezoo.org/meet_our_animals/conservation/boreal_toad_conservation/

https://thelivingplanet.com/boreal-toad-conservation/

Conclusion

Amphibians are just amazing! We’ve learned about what traits all amphibians share and different types of amphibians, we’ve learned how to identify species that can be found in the canyons and have investigated some of the other species that live in the state, and finally we have learned about their importance, some of the threats that they face, and ways that we can look out for our amphibian friends. With your new knowledge, we hope you have a new appreciation for our slippery friends and when you get a chance, we hope that you can visit the canyons to observe their habitats and maybe even see or hear one of our local species.

Let’s play a little game!

Now that you’re an expert on Utah’s Amphibians, print out the Amphibians of Utah poster from the Utah DNR and Utah’s Hogle Zoo to remind you of all the awesome species that can be found in the state!

Download the Student Activity Guide

Sources

Loveland Living Planet Aquarium. (21 July 2021). Boreal Toad Conservation. https://thelivingplanet.com/boreal-toad-conservation/

National Park Service. (n.d.). Series: Reptiles and Amphibians of the American Southwest. https://www.nps.gov/articles/series.htm?id=DF30F97C-D1A7-3773-F4C04F52B6905191

Sageland Collaborative. (n.d). Amphibian and Aquatic Habitat Assessments. https://sagelandcollaborative.org/aquatic-habitat-assessments

Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. (2019). Utah Species field guide. https://fieldguide.wildlife.utah.gov/?class=amphibia

Utah’s Hogle Zoo. (n.d). Boreal Toad Conservation. https://www.hoglezoo.org/meet_our_animals/conservation/boreal_toad_conservation/

Utah’s Hogle Zoo. (n.d.). Tiger Salamander. https://www.hoglezoo.org/meet_our_animals/animal_finder/tiger_salamander/